On May 9, 1894, much of downtown Norway burned to the ground when a fire started at the C.B. Cummings mill, just across Pennesseewassee Stream from the business district. An unusually strong wind spread the fire quickly, destroying almost every building in its path.

This story appeared in the May 12, 1939 edition of the Advertiser-Democrat, to mark the anniversary of the Great Fire of Norway, written by one who was there. The location of some of the places Mr. Sanborn speaks of are:

Stone’s Drug Store – The Tribune Book Store

Pratt’s Bakery – Current location of the post office

Bradbury House – The south end of the Norway Savings Bank Operations Center

Hathaway House and Noyes Drug Store – Either side of Oak Avenue on Main Street

Tubbs’ Store – Cumberland Farms

Steep Falls – The neighborhood around Aubuchon Hardware

Lower Primary Schoolhouse – Near the intersection of Main and Fair Streets

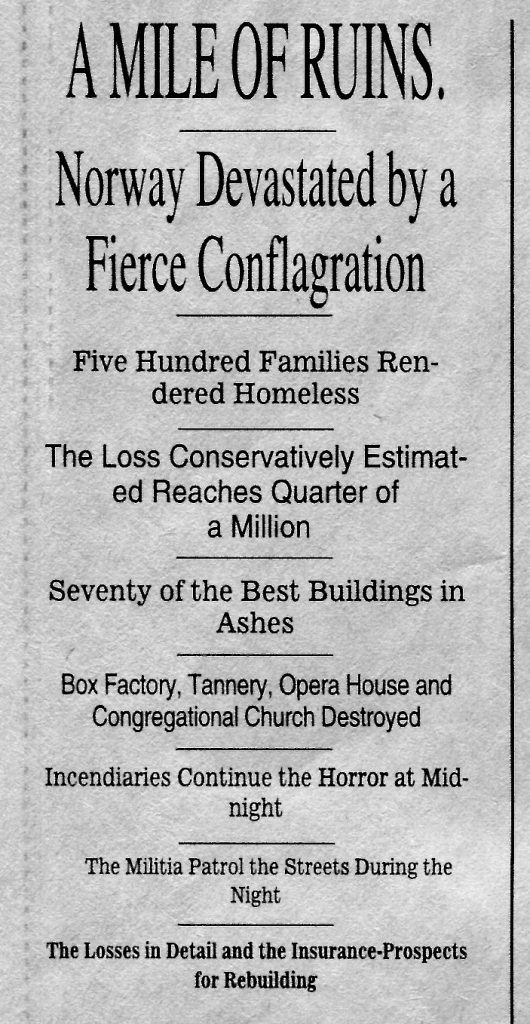

Just a Memory Now (Of May 9,1894 – The Great Norway Fire)

By: Walter L. Sanborn Lansdale, Florida

Tuesday was the forty-fifth anniversary of the big fire that swept away the southerly side of Main St in Norway from Stone’s Drug Store to the Lower Primary School. The opposite side suffered loss from Tannery Bridge to the Henry B. Foster house. This occurred May 9,1894 and the memory of that day lingers.

The writer is one of those whose memory goes back there and he holds the “Norway fire” the most vivid recollection of his youth.

I recall the day as hot, with a strong breeze blowing down Main St. Then in my fifteenth year, I was employed at Deacon Pratt’s bakery, which was about where “Freel” Howe’s music store was the last time I was in Norway.

We went to work in the wee, small hours, after the manner of bakers, and had finished for the day about 1 p.m. on May 9, 1894. The fire signal had sounded and, for some reason or other, instead of running to the fire as everyone else did, I sat down on the stone step of the bakery to see what would happen.

Already a tremendous volume of the blackest sort of smoke was rolling up over Dr. Bradbury’s barn and someone said Cummings’ mill was burning. I remember everyone was in the upper end of the town, though the high wind was carrying burning shingles south in a steady procession. These were so numerous that I, though only a boy, became frightened of the consequences.

When I saw the firemen under Chief Cole making a desperate stand to save the Bradbury buildings, I became seriously worried, a concern that was intensified by the fact that the fire had already communicated to the roof of George Hathaway’s home and the Noyes Drug Store.

The firemen continued to fight a losing battle with a rapidly failing water supply long after the whole row of houses on the west side of Main Street were in flames.

The firemen continued to fight a losing battle with a rapidly failing water supply long after the whole row of houses on the west side of Main Street were in flames.

The heat that swept down on me at the bakery steps was intense, though I did not consider myself in the slightest danger. The truth is, I was simply entranced with the drama of the fire and the terrible thing which I felt inside was happening to my Norway.

It may have been 2:30 o’clock when the realization suddenly swept over me that I ought to go home. Steep Falls was much farther away than I realized. As far down the west side of Main Street as I could see everything appeared on fire. I made my way along the east side of the street to the Tannery Bridge, or nearly to that point. Then I discovered that the tannery was a roaring furnace and passage, even in the middle of the street, was barred by the intensity of the heat. So I backtracked to Tubbs’ Store and hiked, now thoroughly frightened, out Lynn Street to Tucker and thence to the Falls, along the back ways, all the time watching the smoke as it rose along Main Street, as the fire swept everything before it.

I never knew how the flames came to spare the Holmes place, jumping it to raze the homes of Uncle Jock Whitehouse and Put Richardson. Neither do I understand why it stopped at the Lower Primary schoolhouse, except perhaps the vacant lot between the Richardson place and the school supplied a barrier. The way the embers were flying over head, some of them whole shingles that were a mass of flames, it seemed impossible that anything in the path of the fire could escape.

When I arrived at the house, I found things in an uproar. The family was worried about me, but too much occupied with the emergency to make a search. My older brother, Bert, had arrived home some time before I did. He and father had ladders on the roof and had, as I recall, extinguished several incipient fires communicated by flaming embers. There was hardly any water pressure at that end of town by that time. It certainly took a long time to fill a bucket.

That evening I got another thrill when I was permitted to go up town but with the strict admonition not to touch a thing and to mind my own business. It was easy for an open-mouthed youngster to obey both commands. The soldiers were patrolling the streets everywhere. Did they make a ferocious appearance on my young mind, accustomed to such peaceful pursuits as Latin and algebra and dishing lemon pies.

It has always seemed to me the village authorities handled the fire crisis well. There were crowds on the streets early and more came pouring into town every minute until late into the night. There was no sign of disorder and, so far as I ever have heard, no thievery, though household goods were piled hit or miss on lawns and even on the sidewalks, just as they were dragged out by terrified tenants, and just as quickly abandoned, partly because of the heat and more often because of the sense utter helplessness that seized everyone sooner or later on that terrible afternoon.

I recall particularly the vault of the Norway National Bank as it stood amid the smoking ruins of the Norway Opera House. There was a great deal of interesting speculation as to whether it was possible that the records and paper money were still intact. It developed later that they were.

As I remember it now, there was plenty of tense excitement among those burned out that afternoon, but it seems to me that few if any lost their heads. I know of none. I returned home late in the evening and was told to go to bed, though that was the last thing I could think of that I wanted to do. I lay long awake, listening to the seemingly ceaseless babble of voices on the street and running over in my own mind the swift train of events that made up Norway’s greatest community tragedy.

To be sure, better and more modern structures replaced those that were burned and, speaking broadly, the insurance companies footed the cost of the improvements. It has taken nearly a half century to restore the shade.

The town was fortunate in the buildings that escaped the fire, shoe shops, for instance, which meant employment and wages. And there was plenty of excitement in watching the town rise, better and more pretentious than ever, from the ruins.

Yes, the memory does linger in the mind of one small boy. He has since seen nothing that seems on him to compare, though he saw Chelsea, Mass., burn some years later. It must have been the plastic mind of youth. May 9, 1939

The tall undamaged building in the center currently houses The Tribune bookstore. The former Advertiser-Democrat is the white building beyond.

A view of Main Street immediately after the Great Fire. The picture was taken from the corner of Main and Cottage Streets, looking toward Pike’s Hill. The chimney standing at center was at the Cummings Mill, where the fire started.

A view of Main Street looking back toward the center of town. Taken from about Marston Street.

The tall building at the center is Beal’s Hotel, at the corner of Cottage and Main Streets. Taken from the mill yard, where the fire started.