A Town’s Memorial – Norway Pine Grove

A Talk Before the Norway Historical Society

By Larry Glatz

March 20, 2002

Some memorials are physical, like stones and markers; others come in the form of books or journals; and still others exist only in our minds – at least as long as those minds remain active and aware. The subject of my talk this evening, the Norway Pine Grove Cemetery, exists in all three modes. I plan tonight to speak a bit about the stones and markers of Pine Grove and also about the written remembrances, and finally I will make a plea for the preservation of some memories which I fear may slip entirely away unless we are able soon to give them the attention they deserve.

Let me start with the book – the Genesis, Exodus and Leviticus of Norway history, Norway in the Forties, by Dr. Osgood N. Bradbury. Here is a reading from episode number ninety-five, which appeared in the Advertiser of February 15, 1889. It concerns Jonathan Whitehouse, who came to play a very important role in the history of Pine Grove. Bradbury’s story begins with Jonathan’s father-in-law to be:

Pioneer Benjamin Herring was becoming old and broken by the hardships and severe labors of forest clearing, and his aged wife, the mother of his eleven children, had about closed up her labors in this world, while their oldest daughter, Esther, at the age of fifty was a great invalid, requiring much care and watchfulness to protect her from harm, and his Harriet, the last of the daughters of his house, was his only stay and support. And now here comes the inevitable “young man” to beckon her away and leave them desolate.

What could they do! The old people had long and anxious consultations upon the serious situation in which events placed them.

In this dilemma, the old story of the Patriarch Jacob and of Laban the Syrian comes to their aid.

If the “young man” would remain on the old farm, care for the old people and the invalid daughter, he should have the last daughter of the family, the Harriet of his choice, to be his wife, and with her the old homestead on which they had lived and labored for nearly half a century.

The arrangement was a pleasant one for all parties, and on March 8, 1835, Harriet, the last daughter of Benjamin Herring the pioneer, became the wife of Jonathan Whitehouse, who immediately took charge of affairs on the old place….

Jonathan and Harriet lived on the homestead thirty-five years, or until 1870, when he sold and came to the village and bought the Samuel Merrill place at the falls on the right going down, the third house above the schoolhouse. In that house his wife Harriet died in 1882, on November 10, and he laid her away tenderly in Pine Grove.

And this is the man, now becoming bent with the winters of his life, so well known to the comers and goers at the quiet Grove among the Pines—the well-known house builder for our friends that are called away. He is always at home and jolly as he sweeps the streets and cares for the houses in that pleasant city. And it would almost seem that times and events in the past were specially ordered to prepare his mind for the work, and bring [that] man to [that] place when the laborer was wanted.

So Jonathan Whitehouse became the sexton of Pine Grove, and among the many burials he performed was that of his own wife, Harriet, as described above, in 1882.

In another edisode, number fifteen, of February 4, 1887, Dr. Bradbury speaks again of Jonathan Whitehouse. He says:

Wandering in Pine Grove Cemetery one day last summer, I discovered the old Grave Digger busy at his wonted employment, whistling quietly to himself, or humming snatches of some familiar tune, while he wielded his pick and spade and slowly built the house for the final resting place of some fellow traveler, who had at last ended his wandering and come home to rest and sleep. Seating myself on a neighboring grave, I quietly and patiently listened while the singing and the work went on. As he leaned upon his spade to rest his aged limbs, I remarked that he was engaged in a lonesome and unpleasant business, digging graves for his neighbors and friends.

“Lonesome,” repeated he, and he looked up and laughed in his quiet way, “Why sir, in the street of yonder village I know but a few of the people I meet, while here, I know them nearly everyone. There they are strangers, or if known to me, it is in many cases only by name, while here I meet the dear friends of my youth, my neighbors and companions of my younger days. Why, pray, should I be lonesome here? As I walk these paths, gather in the grass of June or the autumn leaves, my old friends whose graves I have made and whose silent forms I have helped lay away hereabouts, come at my call, one by one, and I see them as of old and talk with them of the thoughtless times when our years were few; and they cheer my heart, and I am happy as I think that soon, quite soon, perhaps someone will kindly help me away to sleep among them.

“Lonesome? Why sir, I am happy as the day is long, if I can be busy here. Over yonder the wife of my youth lies sleeping and waiting, waiting patiently till I come. Many are the communings I have with her when the place is quiet, and the bustling day gives place to the setting sun, and the gracious evening calm comes in among these days. Who could be lonesome, sir, with his friends all about him, where he could chat and talk with them as I do here?”

Of course during the Victorian era, when Bradbury was writing his articles, building cemeteries and visiting cemeteries were much more common and important activities than they are today. With all the other diversions available to us now, it seems as if the last thing most people would want to do is visit a cemetery, or at least to visit a cemetery which had no immediate kin within it. This is unfortunate, because cemeteries are such tangible and significant social and historical artifacts. For many smaller communities – which do not have the wherewithal to erect Staues of Liberty or Golden Gate Bridges, or even large wooden scultures of Indians, or lumbermen, or perhaps even gigantic snowshoes – the cemetery is the memorial to the community and its people.

Norway, like most New England towns, has a number of cemeteries, each of which makes a slightly different cultural and historical statement. Anyone who has visited the charming little Upton family cemetery, or the cozy Chapel cemetery in North Norway, or perhaps the simple but proud Norway Center cemetery, which looks grandly across the valley at the rival Pioneer cemetery on Paris Hill, will appreciate this immediately.

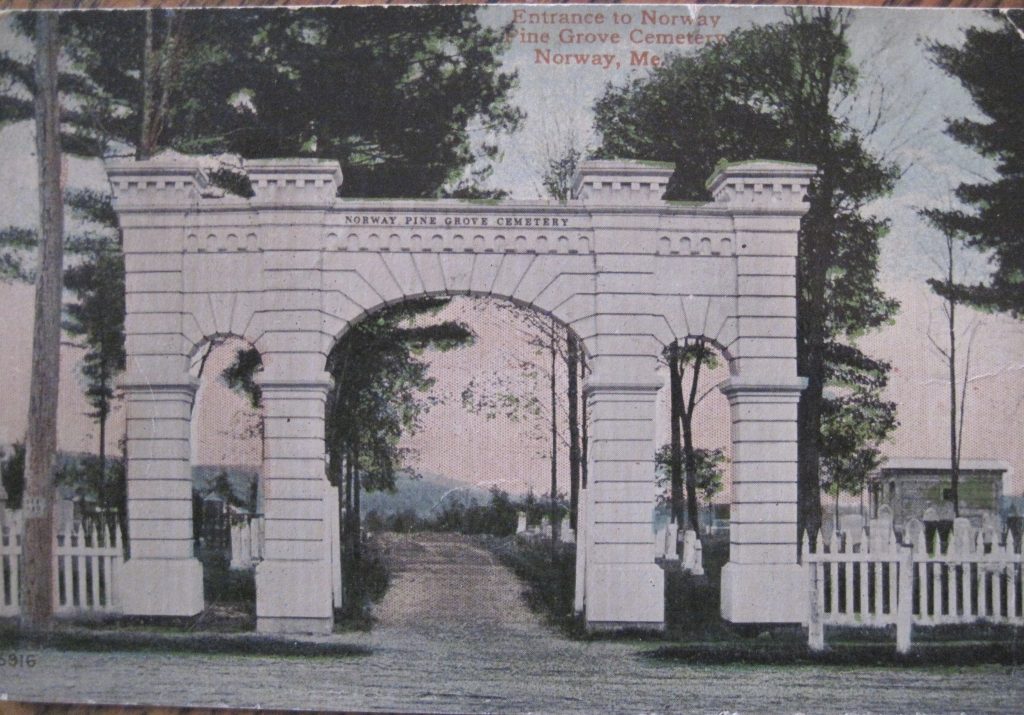

However, Norway’s largest cemetery, Pine Grove, has played a role in the history of this town—and of neighboring towns as well—which is remarkable and unusual. From the date that it opened, in the summer of 1860, until today, when it is about to close its gates to new arrivals (who will, I am sure, not be too disappointed with the beautiful view out over Hobbs Pond from the new Lakeview Cemetery on Watson Road), Norway Pine Grove virtually ended interments at all of Norway’s older and smaller lots.

The events surrounding the formation of Norway Pine Grove also brought to a halt just about every civil conversation between Norwegians and Parisians at that time, and for a brief period it captured the attention of the entire state. We do not have time this evening to describe all of the details of the three year border war between Norway and Paris—full of sound and fury, but thankfully free of bloodshed—but I would like to review just the highlights of the affair.

Back in the 1790’s and early 1800’s, when the original settlers of ancient Norway had need for only a single mill at the foot of the lake, and their neighbors in Paris were similarly served by a small water power on the Little Androscoggin, all of the valuable property was on the highlands—where the soil was richer and the growing season was longer. At that time, the communities known generally as “Norway” and “Paris” were eight or nine miles apart, and no one cared too much about their joint borderlands along the river. In fact, a large piece of this territory was set aside as a fairground, to be used for only a few weeks each year for essentially recreational purposes.

But within the next few decades, as industry came to the area and especially as the Atlantic & St. Lawrence laid its track through the valley in 1849 and 1850, the population centers of each town drifted inexorably from the highlands down to the lowlands; and what we might call the “face” of the village of Norway found itself pushed up against what some felt to be the “bottom side” of the town of Paris. In addition, there was growing development of the property in the southwest corner of Paris by folks who found themselves economically connected to Norway village and who apparently objected to paying their taxes to a community from which they did not feel particularly connected. (Although I have not been able to research the question enough to tell, I also suspect that the tax rates in Paris in the 1850’s were somewhat higher than in Norway, because I simply cannot imagine political energy flowing any other way than toward lower taxes. The nearness of the Norway churches and schools may also have played a role in this.)

One particularly disgruntled and reluctant semi-Parisian was Titus Olcott Brown, Jr., whose rather large estate had its residence in Norway but its outer acres extending into Paris. Mr. Brown, in conjunction with Maj. Henry W. Millett, Norway’s representative to Augusta in 1858 and 1859, thought that it would be convenient for the residents of Norway to have another several hundred acres of land into which to expand, so Maj. Millett shepherded through the legislature in March of 1859, Special Bill, Chapter 301, which granted lots six, seven and eight along the westerly border of Paris to the town of Norway. Norway historian Charles F. Whitman says that Norway’s gain and Paris’s loss could be attributed to the legislative skill of the Major as compared to that of the Parisian representative. This is quite a statement considering that one of the most vociferous opponents on the other side was one Hannibal Hamlin, then of Hampden, in Penobscot County, but a Parisian through and through. However, it probably did not hurt Norway’s cause that in Titus O. Brown’s family was John B. Brown of Portland, who was one of the wealthiest and most influential businessmen in the state at the time and who had business holdings in Norway at the time. In addition, Paris’s case was considerably weakened by the fact that Paris, itself, had used the same plea of the “convenience” of its citizens to persuade the legislature to grant it parts of Hebron in 1818, Oxford in 1838 and Woodstock in 1841. In fact, Paris seems to have been a past master at the land annexation game, whereas this was the first, and proved to be the only, such venture by Norway against any another incorporated town.

It must also be noted that Norway had lost out to Paris in the first battle for the county seat in 1805, and in the much more important battle for the location of the railroad line, in 1850, so it should not have hurt Paris too, too much to have been a bit more generous in this latest matter.[i]

In any event, in 1859, Norway asked the legislature for five new lots of land and ended up with three, while Paris ended up with humiliation—at least temporarily. However, unlike Hebron, Oxford and Woodstock, which had acquiesced to Paris’s land grabs of earlier years, in the next (1860) legislature, the Parisians mounted a vigorous counter-attack, which received even more attention than did the first squabble. During the house debate on Paris’s petition to reclaim the land lost a year earlier, as reported in the Democrat,

There was intense anxiety manifested by the parties, as depicted upon their countenances. Many ladies were upon the floor of the house, and the galleries were filled. (24 Feb 1860)

But Norway prevailed once again, as Paris’s petition was denied on a vote of 61 for and 62 against. But a year later, in March of 1861 (with a much larger civil dispute about to erupt at Fort Sumter in South Carolina) the legislature apparently wanted to quell disputes at home and adopted the recommendation of a special commission that “split the baby” between the two jealous parents. In the end, Norway acquired slightly less than half of the original five hundred acre grant; but at least now included in its domain was the entire estate of Titus O. Brown, Jr. The final boundary was described as follows:

Beginning in the northerly line of lot number eight, at the center of the Old Rumford Road, so called; thence following said center southerly till it intersects the road from Norway to South Paris; thence in a straight line through the agricultural grounds to the southeast corner thereof; thence in a straight line to the northeasterly corner of Titus O. Brown’s homestead farm, so called; thence to the easterly line of his said farm to the Little Androscoggin river, and thence by said river westerly to the original line between Paris and Norway.ii]

But there was something else of significance to us here this evening going on in 1860, when Norway was at its largest and the Parisians were withdrawn to the hill, skulking in their tents and planning reconquest.

About that time, a group of citizens, realizing that the Rustfield cemetery in the heart of the village, as well as the smaller cemeteries in the other parts of town, were running out of room, thought that an ideal place for a large new cemetery would be found in the vast new expanse of Norwegian territory to the east of the fairgrounds, situated in a beautiful grove of Norway Pines and overlooking the meandering river valley. (And anyhow, Paris had a nice cemetery on the river, so why shouldn’t Norway?) Therefore, an association was formed, the land was acquired, the new cemetery was incorporated and on June 17, 1860, Mrs. Isabelle Tuttle—a Parisian, it must be noted—became the first permanent resident of Norway Pine Grove cemetery.

Now, a hundred and forty years later, among the six thousand or so “houses,” as Bradbury called them, which are there in “that pleasant city,” are some belonging to people who were known across America and some who, being known perhaps only to a small group of friends and relatives who have now also passed away, are known no more. But before the memories fade any further on these folks and on Norway Pine Grove altogether, I want to urge that we take some modest steps to memorialize this memorial ground.

I would like to suggest that we pick up from where Father Don McAllister left off with his recent walking tour of Pine Grove. I hope we could agree that, at the very least, we should create a one-page guide to the notable features of the cemetery which would be available to visitors at any time. There could be available at the society, the library, the Maine Discovery store and also at the Chamber office, which is, after all, directly across the street from Pine Grove. (I might also recommend that a cross-walk be painted somewhere along the vast length of the cemetery, since now there is none, and crossing Route 26 is as likely to make one a resident of the graveyard as a visitor there.)

Also, within the cemetery we should erect a number of historical markers, similar to those which the Downtown Revitalization people have placed on some of the Main Street buildings. I’m not suggesting that we have a marker for every person or incident which I will mention tonight, but I hope you will agree that it would be well worth the effort to create a public and enduring record of maybe a half dozen of the more important cultural artifacts of our town. Just some of the possibilities are these:

Although the cemetery opened in 1860, there are well over a hundred graves there of people who died well before that time. Ben Conant tells me that when the newer part of the Riverside Cemetery in Paris opened, the residents of entire smaller cemeteries from outlying neighborhoods were moved to new sites in Riverside. The records suggest that at least five or six complete cemeteries were moved, probably so that the surviving relatives could be sure that the gravesites would enjoy “perpetual care” which would only be available in the newer lot. At any rate, it is clear that many older graves were also moved to Pine Grove over the years. Although there may be earlier “relocations” than the ones I have found, Walter Bullen, a two year old child who died in 1810 may be earliest of them all. One Sarah A. Martin, a fourteen year old girl who died in 1812 is also there. At first, when consulting the Pine Grove directory, which was compiled by Fern Clark and Grace Emmerton in 1985, I noted that their record of the death of E.F. Beal in 1811 would make him one of the most ancient people in the lot; however in comparing this information with other sources, I found that E.F. Beal (that is Ezra Fluent Beal, the father of General George Lafayette Beal), died not in 1811, but in 1871. Perhaps the gravestone inscription had weathered away, perhaps the compilers misread their notes when typing up the directory, or perhaps a simple typo explains the matter. Whatever the cause, it is important to keep in mind that directories of gravestones are not necessarily identical to the gravestones they describe, and the information on the gravestone itself, although actually “set in stone,” is not impervious to change over the years.

There are also a number of markers for people who whose remains are, in fact, elsewhere. These include James Abbott, who was buried in New Hampshire, William W. Abbott, who rests in Upton, Maine, and Lt. Robert Emerson, who was lost in a flight over the Philippines in 1945.

There are markers for people whose whereabouts remain unknown. Just one of these is C.A. Stephens’s grandson, Steve Delano, whose ashes were supposedly shipped from a funeral home in Boston to one in Norway, but their final disposition is undocumented, in spite of the fact that there is a headstone with his name on it in the family plot.[iii]

Pine Grove is the final resting place of no fewer than 175 war veterans whose graves are marked to indicate their service records. These include at least one from the Revolutionary War, seventy-three from the Civil War, forty-five each from World Wars I and II, and some also from the Spanish-American War, the Korean War and Vietnam. But there are lots more war veterans whose graves are not so marked. For example, there is no indication that any soldier who served in the momentous Aroostook War rests in Pine Grove, but Norway raised a company of men and marched them as far as Augusta to stand up for Maine in that conflict, and at least three of them, including their captain, Amos F. Noyes, are in Pine Grove with no memorial to their almost participation in that almost war.[iv]

By comparing William Lapham’s list of veterans against the Pine Grove records, I found two soldiers from the War of 1812 and at least twenty-six from the Civil War who lie with no veteran’s marker.[v] Who knows how many from other wars may be there? Some of those whose service records are not noted are Cyrus Tucker, who was the brigade saddler with the 17th Maine, William Whitmarsh, who was a sergeant with the 1st Maine, a lieutenant with the 10th and finally a captain with the 23rd.  There is also not a single notation on any of the veterans’ graves of service in the unusual private company which was raised by Capt. Sylvanus Cobb, Jr.[vi] And although the gravesite of George Lafayette Beal displays a humble, rusted GAR stanchion, the only suggestion that this is the burial place of the man who was probably Norway’s most important military figure is the vacant pedestal of some kind of marker which seems to have been stolen. [vii]

There is also not a single notation on any of the veterans’ graves of service in the unusual private company which was raised by Capt. Sylvanus Cobb, Jr.[vi] And although the gravesite of George Lafayette Beal displays a humble, rusted GAR stanchion, the only suggestion that this is the burial place of the man who was probably Norway’s most important military figure is the vacant pedestal of some kind of marker which seems to have been stolen. [vii]

Aside from those who are buried with no indication of important circumstances of their lives, there are a number whose biographies are described in just enough detail to make us want to find out more. These include: Hosea P. Aldrich, 1834-1919, who is identified as an “inventor,” and Atherton B. Furlong, 1849-1919, “artist, singer, poet.” Most notable in this regard is the imposing monument to Rev. Thomas Barnes, 1750-1816, which identifies him as Norway’s first Universalist minister. But what the stone does not say is that Rev. Barnes was one of the very earliest ordained ministers in the history of the Universalist church and that he is considered by some to be one of the founding fathers of that faith.[viii]

We especially need to do something to commemorate the gravesite of Mellie Dunham, who rests over a knoll in the far southwest corner of Pine Grove, far from sight and getting further and further from mind.

We especially need to do something to commemorate the gravesite of Mellie Dunham, who rests over a knoll in the far southwest corner of Pine Grove, far from sight and getting further and further from mind.

Also, the large mausoleum with only the name Thompson upon it needs a descriptive notice. Norwegians need to be reminded of the family of Maude Thompson Kaemmerling, whose remarkable generosity gave us the original library building, the town beach and a large infusion of seed money for the hospital—not to mention the largest of all monuments in the cemetery, and the second-largest, as well, as I will describe later.

We might also remember Jonathan Blake, the Diamond National man, L.F. Pike, the elixir man, Vivian Akers, the artist, Hugh Pendexter, the writer, and Minnie Libby, the nationally known photographer.

There is Clarence Smith, whose brother (Sidney I. Smith) became a noted naturalist, whose sister married another noted naturalist (Addison E. Verrill) and who, himself, achieved local acclaim as the center fielder on the Penneesseewassee Base Ball Club of 1867, which defeated Bowdoin to bring home the “silver-ball” as state champions. Clarence Smith was also one of the forgotten band who volunteered with Captain Sylvanus Cobb’s private company in the Civil War, and he is one of the even more forgotten band who populated the factory at Norway Steep Falls which made—believe it or not—some of the most sought-after piano-keys in the nation. And this same Clarence Smith, we are told, developed the original forms for manufacturing the turned up toe that made Norway’s snowshoes famous. Is there a person more deserving of a memorial than the now completely forgotten Clarence Montrose Smith (1846-1923)?[ix]

Speaking of snowshoe men, Pine Grove is home not only to Mellie Dunham, but also to “Bert” Hosmer, who put a turned up heel on his so-called “Sag-No-More” snowshoes and gave the Tubbs company a run. There is Bert’s father, Herbert Henry Hosmer, who, according to his obituary in the Advertiser of February 10, 1933:

…was an expert trapper, woodsman and guide and served as fire warden on Mt. Caribou during the world war… In 1890 he went west and worked as a cow puncher. Returning to Norway he traveled with Wild West shows during 1892-3 and received an offer from Buffalo Bill’s show which was not accepted. His specialty was roping and fancy rifle and pistol shooting.

For many years he played a violin with the late Mellie Dunham at country dances and had been a contestant in old-fashioned fiddling contests when they were popular.

Another noted rifle man was Capt. Moses P. Stiles, who was the national champion marksman in 1908 and was named to the American Olympic team in 1912, but unfortunately could not afford to leave work for the long trip to Sweden (the country, that is). His wife, Myrtie, was one of the four Jordan sisters. They all lived right in this neighborhood (the neighborhood of the Norway Historical Society, that is) for much of their lives and have since gathered their husbands with them into Pine Grove. Myrtie’s twin sister, Mattie, was married to Stephen B. Cummings, one of the “sons” of C.B. Cummings “and Sons.” Mr. Cummings, according to his obituary notice, “was an outstanding amateur astronomer and collected many valuable photographs of celestial bodies.” Annie Jordan was the wife of Frank Beck, who built the building beside Barjo’s and ran it as Beck’s Bazaar (or some say, it ran him—right out of business); and the youngest Jordan sister, Lydia, had perhaps the most celestial or maybe bizarre life of them all. She married Dr. James Littlefield and moved with him to Paris Hill, where the couple made national headlines when they were cruelly murdered in October, 1937.

There is John L. Horne, the tannery man and his daughter-in-law, Fanny Holmes Horne, who was the long-time organist at the Congregational Church and will be mentioned in more detail later. There is Mark P. Smith, who sold the tannery to John Horne in the first place and in whose house (i.e. the Norway Historical Society building) we sojourn here this evening. There is Frank Bjorkland, Finnish consul and noted baritone; Titus O. Brown, who began the whole Pine Grove affair, and let us not forget Jonathan Whitehouse, whose humane and caring deeds were noted above.

We might also note the legend of Indians buried nearby, perhaps on the edge of Titus O. Brown’s property, now Brown Street, where it meets the river, or perhaps below the fairgrounds, or perhaps even on the southern slopes of Pine Grove itself. I have looked hard but have not found any contemporary reference to this site, but Osgood Bradbury says in his article of July 22, 1887, that “some ten years since,” that is about 1877, an Indian burial ground was discovered somewhere between the Steep Falls, so called, and the Pine Grove lot. At that time, Bradbury was worried that the site might be forgotten, and he said:

I do not know that the bones of the people that once lived here have been discovered in any other locality in town, hence their high bank with the moaning pines scattered in profusion near it is the only place where these “very first” settlers lie buried. And this scribe in all sincerity would suggest that a half acre of land be purchased, and some boulder of large weight, or some rough block of the granite of the country to well typify the Indian character, such as many oxen might haul, be taken to the place and be put in the right position with the proper inscription upon it, to perpetuate the memory of those stern old “red men” who performed their life’s allotted task, and graciously crept into their graves at the proper time without a murmur or complaint…. A deed should be taken of the land and properly recorded. The corners should be marked by four rough granite posts, set well in the earth, and the sides might be marked by four others. What three young gentlemen, or young ladies of our village will see this work done? Here’s a dollar to commence a subscription.

In addition to the residents of “that pleasant city,” it would be helpful to know something more about many of the little houses in which they dwell. The tombs: the Brown tomb, the first Thompson tomb, which is now the town holding vault, and the second Thompson tomb, which is the third and final resting place of Frank Thompson, the brother of Maude Thompson Kaemmerling. When Frank’s father, Albert Thompson lost a leg in a saw mill accident and took up dentistry as a profession, he turned his family’s substantial lumber interests over to his son, a recent Dartmouth graduate, who ran them with perhaps a bit too much efficiency. In March of 1897, Frank was shot to death by a disgruntled business rival in West Virginia. He was taken to the nearest hospital, in Cumberland, Maryland, where doctors kept him alive for a few days; and when he died a special train carried his body back to Norway, where he was buried in Rustfield Cemetery until this great mausoleum could be constructed in Pine Grove. Then, shortly before her own death in 1957, Maude Thompson Kaemmerling donated the first tomb to the town for a community holding vault and constructed an even more stately edifice on the eastern edge of the cemetery, where her brother, Frank, has found his final quiet rest.

There is also the curious mill-wheel stone of (I think) the MacIntyres, the large stone gateway of the John F. Crockett lot, the “little chair” of the Kerr-Loring family, the small angel which

There is also the curious mill-wheel stone of (I think) the MacIntyres, the large stone gateway of the John F. Crockett lot, the “little chair” of the Kerr-Loring family, the small angel which  looks over the “baby lot,” and the large angel which appropriately symbolizes the very considerable financial angel which Zeb Merchant was to the town—particularly to the hospital, and to the cemetery itself. In fact, Zeb was so committed to the notion that Norway Pine Grove’s perpetual care fund should reach $100,000 in endowments that he left the remainder of his own estate to that cause.

looks over the “baby lot,” and the large angel which appropriately symbolizes the very considerable financial angel which Zeb Merchant was to the town—particularly to the hospital, and to the cemetery itself. In fact, Zeb was so committed to the notion that Norway Pine Grove’s perpetual care fund should reach $100,000 in endowments that he left the remainder of his own estate to that cause.

Let us not miss the two little pink quartz stones near the railroad tracks: one for young John Scothorne and the other for Winona Palmer. There is also at least one remarkable monument in Pine Grove that no one will ever see. It lies beneath the gravestone of Alice Davis, who had no heirs and therefore directed that her entire estate be liquidated for her burial expenses, which, in order to make them large enough to absorb the cash at hand, included, I am told, a burial vault of solid copper.

Let us not miss the two little pink quartz stones near the railroad tracks: one for young John Scothorne and the other for Winona Palmer. There is also at least one remarkable monument in Pine Grove that no one will ever see. It lies beneath the gravestone of Alice Davis, who had no heirs and therefore directed that her entire estate be liquidated for her burial expenses, which, in order to make them large enough to absorb the cash at hand, included, I am told, a burial vault of solid copper.

There is also the modest granite gravestone of Fanny Holmes Horne, daughter-in-law of John L. Horne, the tannery man, mentioned above. Mrs. Horne was the long-time organist at the Congregational Church and undoubtedly accompanied the funeral services of a goodly number of the current residents of Pine Grove. At the same time, she was the local agent for the American Cast Bronze monument company, and the results of her sales—at least forty-seven of /those remarkable metal monuments—adorn the cemetery today. Some time ago, Father Don McAllister photographed all of them, and his album is on the table to look at this evening. Also included with the pictures is a photocopy of the sales brochure from which the memorials were selected. It would be interesting to see if any other cemetery in the state has as many of these remarkable memorials as does Pine Grove. Why Mrs. Holmes did not order one up for herself and her husband must remain another of the mysteries of the cemetery.

And, not quite the last item I need to mention, the Pines, themselves, need a memorial. These are, after all, “Norway Pines,” named for this town, in which the species was first identified. And the grove, itself, represents one of the stateliest stands of Norway pine to be found anywhere. I understand that there is a movement afoot to codify the official name of this tree as the “Red Pine,” because the “Norway” part of the name might be too confusing, what with Norway the town and Norway the country, and all. But we must resist that movement, and all other such movements which seek to erase from our memory the reasons for why things are. (Note: After my talk I was notified by a local naturalist that there are actually no Norway Pines [Pinus resinosa] in the cemetery today. However, Addison Verrill, a noted naturalist of his own day commented in his diary on the “Norway Pines” he saw there in 1860. As an English major rather than a botany major, I don’t dare to comment further.)

And, not quite the last item I need to mention, the Pines, themselves, need a memorial. These are, after all, “Norway Pines,” named for this town, in which the species was first identified. And the grove, itself, represents one of the stateliest stands of Norway pine to be found anywhere. I understand that there is a movement afoot to codify the official name of this tree as the “Red Pine,” because the “Norway” part of the name might be too confusing, what with Norway the town and Norway the country, and all. But we must resist that movement, and all other such movements which seek to erase from our memory the reasons for why things are. (Note: After my talk I was notified by a local naturalist that there are actually no Norway Pines [Pinus resinosa] in the cemetery today. However, Addison Verrill, a noted naturalist of his own day commented in his diary on the “Norway Pines” he saw there in 1860. As an English major rather than a botany major, I don’t dare to comment further.)

So last of all, I would like to suggest that if we remember nothing else at all in Pine Grove, we remember the grave of Dr. Osgood N. Bradbury, himself. It is, as you might expect, a  “boulder of large weight;” it is a “rough block of the granite of the country…, such as many oxen might haul.” It has inscribed upon it only the name “Bradbury,” and a few feet away is another much smaller marker with just the initials “O.N.B., MD.” In the Pine Grove directory, the site is described like this: “Huge chunk of granite; ‘Bradbury;’ no name on it.” [x]

“boulder of large weight;” it is a “rough block of the granite of the country…, such as many oxen might haul.” It has inscribed upon it only the name “Bradbury,” and a few feet away is another much smaller marker with just the initials “O.N.B., MD.” In the Pine Grove directory, the site is described like this: “Huge chunk of granite; ‘Bradbury;’ no name on it.” [x]

So we must remember this man for whom Pine Grove and its residents meant so much, and who memorialized so many of them in his remarkable writings—writings which, as I said at the beginning of this talk—have become the sacred text of Norway’s history. I believe that of all the important sites to commemorate in Pine Grove, we must begin with a simple plaque for Dr. Bradbury.

“And what three young gentlemen or young ladies of our village will see this work done? Here’s a dollar to commence a subscription.”

Thanks to Larry Glatz for the use of this presentation and accompanying photos.

Notes:

[i]. Other inter-town rivalries included: A) In 1825, Norwegians Levi Whitman, Joseph Shackley, Moses Ames and Daniel Young petitioned the legislature for land to be set off from Paris, but failed. [See Jan. 20, 1825 Oxford Observer item on Maine House of Representatives, which says that the petition was read in committee on January 12; see also Lapham’s History of Paris, chronology for 1825.] B) In 1826, Asa Barton conducted a late night removal of his newspaper and printing establishment from Paris Hill to Norway. C) In 1848, there was a question of moving the county buildings from Paris Hill, which failed. D) In 1862, Francis Whitman agitated to have additional Paris property set off to Norway, but the Parisians threatened to counter this move by a demand for a return of the entire 1861 grant. E) In 1877, Norway mounted the most serious effort yet to have the county buildings moved to their town, but the effort again failed. F) In 1892, the county buildings were finally moved from the Hill but remained within the town of Paris, in spite of the demands of many Norwegians.

The town of Norway seemed to carry on an almost endless campaign to have the county buildings moved to their precincts. One interesting example occurred in in February, 1855. At that time citizens of sixteen towns in western Oxford and northern Cumberland Counties petitioned the legislature for permission to form a new county, to be called “Sebago.” The legislature received many petitions, pro and con, on the question. Norway’s suggestion was that the geographic alienation felt by the “bolters” could be easily cured by moving the county buildings just a little to the westward of their then current location—that is, from Paris to Norway. (Disappointed in the first go-round, the same towns petitioned the legislature for separation in 1856, this time asking that the new county be named “Pequawket.” But the legislators didn’t seem to go for this idea either.)

[ii]. See Maine Special Acts of 1861, Chapter 54.

[iii]. As of 1999, Charles Delano’s headstone displayed a date of birth but no date of death. According to the death certificate issued by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, he died in Boston on November 28, 1994, and his cremains were transferred to Norway shortly thereafter. Although the Friends of C.A. Stephens arranged for the date of death to be completed on the gravestone, there is no conclusive evidence that Charles Delano’s remains are actually interred at Pine Grove. The stone is located in the Knower-Delano lot in the west central part of the cemetery. Interestingly, there is also no official record that Carl Boynton, C.A. Stephens’s only other grandchild, was actually buried at Pine Grove, even though there is a military headstone there which records his birth and death.

[iv]. According to Lapham (History of Norway, p. 242), the Aroostook company also included Prescott L. Pike (1815-1891) and Winthrop Stevens (1809-1880), who are buried in Pine Grove. Cyrus Cole and Henry Frost may also be there, but I need to check further to determine this.

[v]. The veterans of the War of 1812 are Ephraim Crockett (1789-1856) and Nathaniel Morse, Jr. (1788-1870). The unmarked graves of Civil War veterans include Jonathan Blake, Caleb C. Buck, David L. Butterfield, Edward W. Bumpus*, Fitzroy Bennett, Horace Cole, William C. Cole, Grosvenor Crockett, Charles B. Cummings, John F. Fitz, David Flood, Jr., Mark F. Frost*, Weston Frost, Gilbert L. Fisk*, Andrew P. Greenleaf*, Charles L. Hathaway, Joseph F. Herrick, Lewis Lovejoy, Edward F. Morse, Charles F. Millett, Francis M. Noble, Charles S. Penley, Jason F. Rowe, Oliver Shackley, Clarence M. Smith, Cyrus S. Tucker, and William W. Whitmarsh. Those marked with asterisks died in the service.

[vi]. By comparing the list of Cobb’s company in Lapham’s History of Norway against the Pine Grove directory, it appears that the following members of the company are at Pine Grove: Lieutenant Claudius Favor, Corporal George A. Cole, Privates Charles B. Cummings, William E. Frost*, Atwood Gammon*, Andrew P. Greenleaf*, Joseph F. Herrick, William F. Merrill*, Charles F. Millett*, Charles S. Penley*, Frank H. Reed*, Oliver Shackley and Clarence M. Smith. Those marked with asterisks also served in other Civil War units, which may be noted on their graves.

[vii]. General Beal’s gravestone is located in the row near Main Street about half way between the Pine Grove entrance gate and the high school fence.

[viii]. The memorial for Hosea P. Aldridge is located in back row of the cemetery about half way between the sexton’s building and the high school fence. I have not yet located Atherton Furlong’s grave. The monument to Rev. Barnes is just in front and to the east of the sexton’s building.

[ix]. For details on the “silver ball” story, see the original news item in the Oxford Democrat of October 25, 1867, the retelling of the tale by C.A. Stephens in the Norway Advertiser of March 21, 1930, p.12, and the follow-up recounting by the last surviving member of the team, Silas H. Burnham, in the Advertiser of July 11, 1930. Note that Mr. Burnham states quite emphatically that the championship game occurred in 1868, but contemporaneous newspaper reports confirm that it actually took place in 1867. (Other members of the championship team buried at Pine Grove are left-fielder Cyrus Tucker and third-baseman James Danforth.) For information on Clarence Smith’s involvement with the development of Norway’s snowshoe industry, see the pamphlet in the “Snowshoe” box at Norway Memorial Library. His association with the piano-key factory is mentioned in an article in the Advertiser-Democrat of August 8, 1952, although the article gives him the middle initial “W” instead of “M”.

[x]. Just to the east of the Bradbury boulder is an identical stone inscribed with the name Jones. This marks the burial place of Dr. George P. Jones (1830-1897), long-time Norway dentist, his wife, Olivia (Stearns) Jones (1829-1901), their son, Dr. Harry P. Jones (1871-1927), and his wife, Emma (1876-1921). Mabel F. Jones, the daughter of George and Olivia Jones married Dr. Bial Francisco (“Frank”) Bradbury (1861-1927), who was the son of Dr. Osgood N. Bradbury. When Mabel died (5 Feb 1897), she was buried on the Bradbury side of the Jones-Bradbury lot. Given the symmetrical design, the impressiveness and the obvious costliness of the Jones-Bradbury memorials, a number of the family members must have been involved in the planning and execution of the installation.