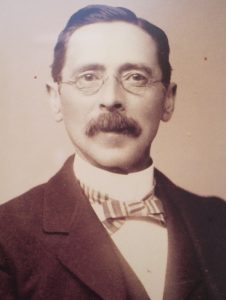

Charles Asbury Stephens – Writer, Traveler and Scientist of Norway, Maine

Charles Asbury Stephens was born in Norway, Maine, on October 21, 1844. His surname at birth was “Stevens,” but he adopted the “ph” spelling very early in his writing career. He said he changed his name to protect his parents from embarrassment should he fail in his public life, and this may indeed have been the case. However, one of the most well-known writers of mid nineteenth century America was Ann S. Stephens (1810-1886) of Portland; and it’s not impossible the young writer from Norway took on the “ph” to associate himself, however tangentially, with that famous person.

Charles Asbury Stephens was born in Norway, Maine, on October 21, 1844. His surname at birth was “Stevens,” but he adopted the “ph” spelling very early in his writing career. He said he changed his name to protect his parents from embarrassment should he fail in his public life, and this may indeed have been the case. However, one of the most well-known writers of mid nineteenth century America was Ann S. Stephens (1810-1886) of Portland; and it’s not impossible the young writer from Norway took on the “ph” to associate himself, however tangentially, with that famous person.

Stephens attended the local Norway schools — first at North Norway and then in the village at the Norway Liberal Institute. His parents were staunch Methodists. (Stephens’ middle name commemorates the first American Methodist bishop.) This likely explains why he was sent for “finishing” to Kents Hill Academy, which had been founded as the Maine Wesleyan Seminary. He entered Bowdoin College in 1866. Halfway through his junior year, he ran out of money. Even though it was winter, he walked from Brunswick back home to Norway, where he chopped wood, sold items door-to-door, did odd jobs, and finally returned to complete his studies by 1869. However, when he learned the college assessed a special fee for graduation, he refused to participate in the event and thus forfeited his degree.

Stephens describes the next step in his career as follows: “… I went out to Kansas for a while but there was no job to be had anywhere. So I bought an ax — the usual answer in dire need — but there was no money in chopping wood. There were no New England trees out there! When I had just enough money left for the cheapest ticket for the shortest way home, I left. I walked the last distance and went directly to my Mother’s pantry and filled up. Then I announced that I had decided to write for a living. My parents sold a cow for the money for me to go to Boston. I set out determined to write. They thought that I would never amount to anything.” (From None But the Best, Louise Harris, private imprint, 1966, p.28)

But, in fact, he amounted to quite a lot. Between 1871 and 1929, Stephens wrote over fifteen hundred stories, primarily for The Youth’s Companion, one of the largest circulation family magazines of the time. Published with him in that magazine were such writers as Jack London, Sarah Orne Jewett, and many others. Many of his most memorable stories concern five orphans of the Civil War who return to their grandparents’ farm in North Norway, where they thrive on rural life and lore.

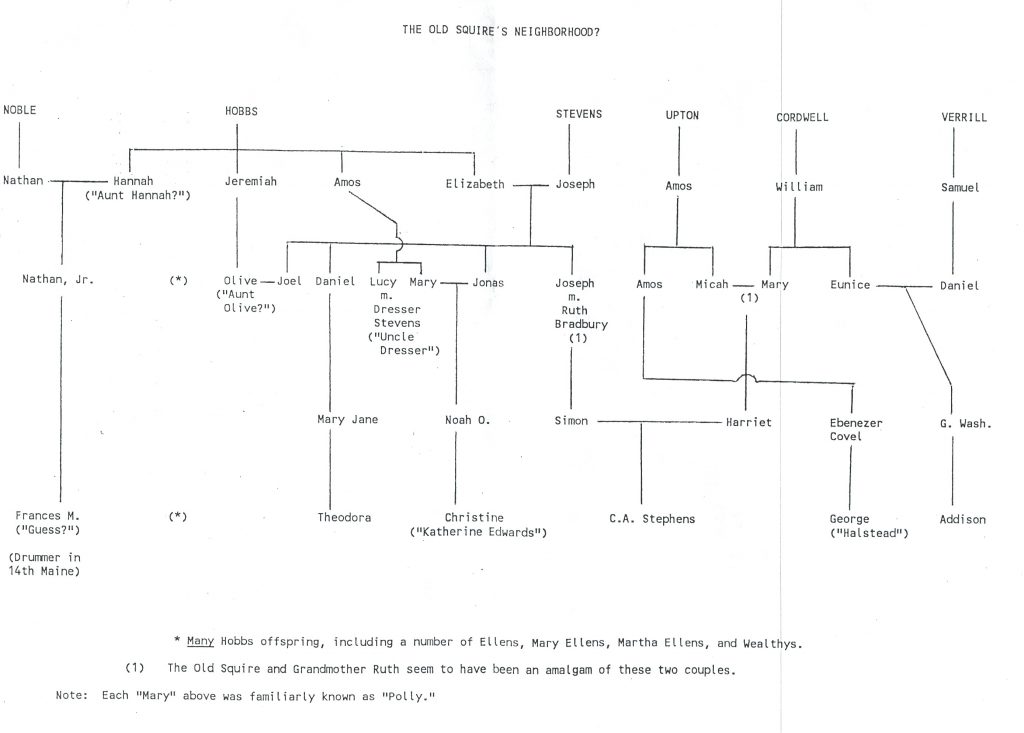

Chart illustrating C.A. Stephens’ relatives and the characters who were likely modeled after them

On assignment from The Youth’s Companion, he traveled the world and filed stories on a myriad of subjects, from searching for baked beans in Archangel, Russia, to capturing a baby elephant in Sumatra. He used over sixty different pen names, including “Zu Behfel,” the German engineer, “Jarvis Stinson,” a sea captain, and “Charlotte H. Smith”, a pioneer settler, whose stories resulted in several proposals of marriage to “Miss Smith” from lonely frontiersmen.

While working in Boston, Stephens decided to undertake medical studies. He earned a doctorate from Boston University in 1887, and spent many years investigating the mechanisms of human aging. Dr. Gerald Gruman of Harvard Medical School described him as “a pioneer of American gerontology.” (Geriatrics, May, 1959.) Stephens’ idea was that humans aged because their individual cells aged; and if this “cell old aging” could be slowed or stopped, life would be correspondingly prolonged. He wrote a number of books on the subject and even told a Bowdoin College official that his writing for “youth” was done primarily to fund his scientific projects. He tried several times to enlist established scientists to come to his Laboratory at Norway Lake to assist in the project, but none responded.

Stephens was an early advocate of women’s suffrage, a national park system, and experiential education. His “Camping Out Series,” which was a great early success, included six books about a group of lads who founded a “Steamship College” to travel the world and discover its natural wonders.

C.A. Stephens’s second wife, Minnie Scalar. Covent Garden Opera photograph taken in 1916

After the death of his first wife in 1911, Stephens married Minne Scalar, of West Paris, Maine, who was an internationally known operatic soprano. She is one of three divas to whom the music room at Portland’s Victorian Mansion museum is dedicated.

C.A. Stephens died in Norway on September 22, 1931, and is buried beside Madame Scalar at the Riverside Cemetery in South Paris. Stephens Memorial Hospital, located in his home town, is named for him.

Stephens’ first wife, Christine Newell Stevens (a second cousin), was a local elementary school teacher who also wrote occasional stories for Portland papers and several national magazines. Later in life, Christine became very active in women’s clubs locally and state-wide. She died in 1911 at the age of 64. A collection of her stories was published in 1997 by the Friends of C.A. Stephens. Christine is buried in the Norway Pine Grove Cemetery.

Collections of C.A. Stephens stories are found in almost every library in the state. Historical archives are at Bowdoin College, Brown University, and the Norway Historical Society.

Article courtesy of Larry Glatz